Foreign, female and changing the face of the NBA

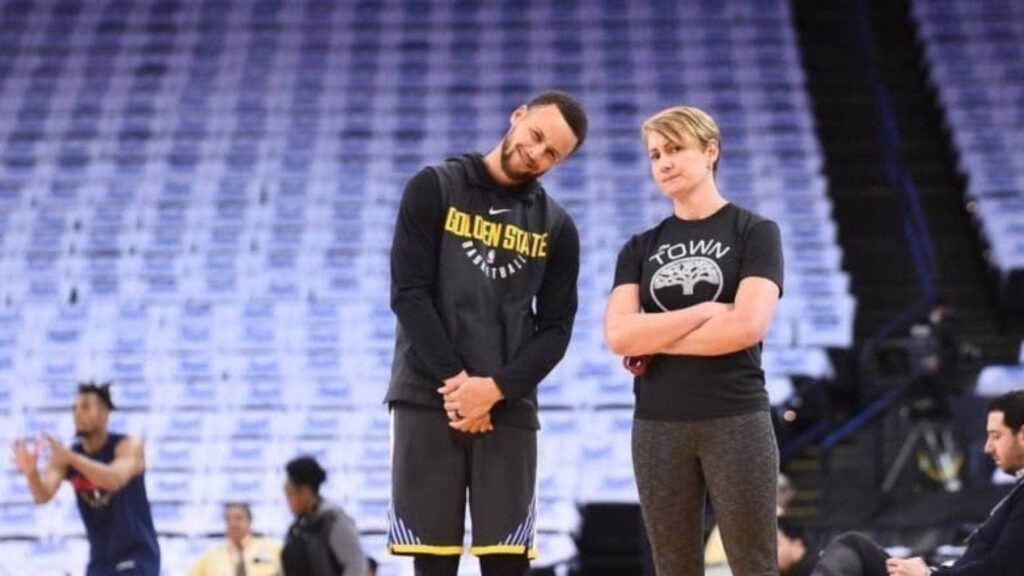

Imagine getting a job with an NBA franchise and not knowing anything about Basketball, then imagine your job wasn’t just with any old franchise but with the Championship winning Golden State Warriors. That was the situation Chelsea Lane found herself in in 2015.

Chelsea trained as a sports physio in Sydney before emigrating to New Zealand in the early 2000s with her Kiwi husband. She worked in a physio practise in the South Island picking up work here and there with high performance athletes before moving to Auckland in 2011 to take up a role with the newly created organisation, High Performance Sport New Zealand. Then one day out of the blue the NBA came knocking.

“I got an email from an American guy asking if I could look at some issues in their programme, that in itself wasn’t out of the ordinary as I did do that sort of work from time to time. But then all of a sudden I was offered a full time job and was moving to San Francisco and joining this crazy world that was the NBA.”

Chelsea says she had only just started to feel like a real ‘Kiwi’ in Aotearoa and the move to the US brought a fresh of culture shock, however as she began navigation her new role and all that came with it she was surprised to realise that the franchise were also trying to navigate their round her.. Specifically her gender.

“When I first arrived I thought my ‘otherness’ was because I was a Kiwi, despite the fact my gender had been brought up on several occasions, I never really believed it was an issue. I had come from a place where being a woman and doing what I do wasn’t unusual so it took me a while to realise in this new climate I was in fact incredibly unique. I was told that the biggest hesitation of bringing me into the team was because I was a woman, and I thought that was absurd, I was like your biggest concern should really be that I know nothing about basketball, you should be concerned about the fact that I literally googled basketball when you offered me the job, who cares if I’m a woman.”

A female management role in the NBA in 2016 was rare, so rare in fact that there were no female toilets, showers or changing rooms. In the early days Chelsa brushed it off, preferring instead to focus on doing her job as best she could but after a while she realised that she had an incredible opportunity to change things for those who would come after her.

“I started receiving lots and lots of letters from little girls – they see you on the television, and they see that you are there with the coaches and you are actually part of the game. Up until that point the only females they have seen have been dancers or entertainers. I would get these letters from girls and the fathers of little girls talking about creating pathways into sport science and it is impossible to not be touched by that. Once I stopped fighting and pretending that my gender was insignificant it was actually easier because I was able to become an advocate. I realised I needed to take this seriously, if I was being judged for being female, if there were no changing rooms or toilets for me, then I had a real opportunity to stop the next person from feeling like that, I had a responsibility for the people who came after me. That I had become a role and I was breaking stereotypes.. I realised I needed to respect that, because it’s a powerful thing.”

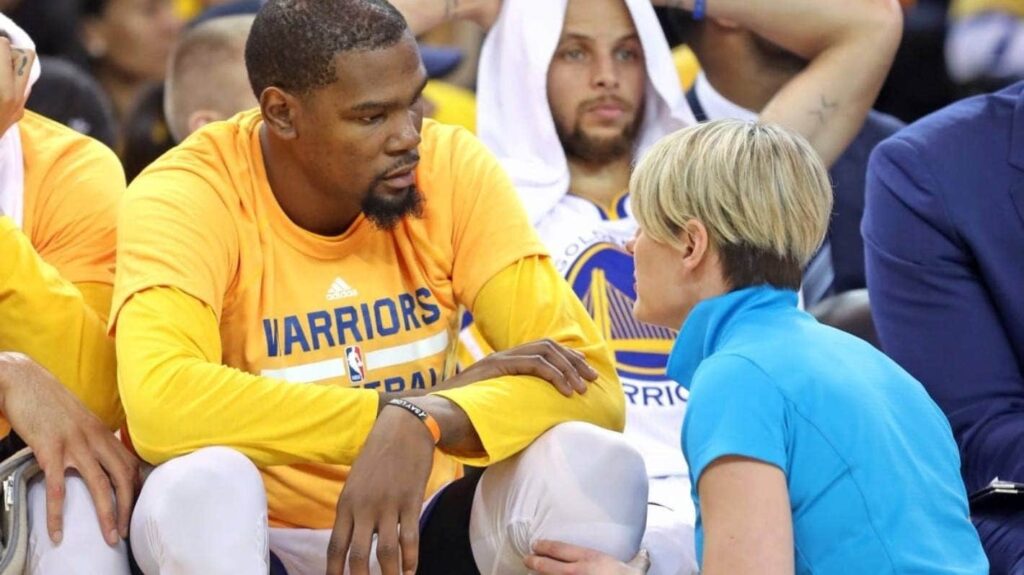

Chelsea was fortunate enough to be part of the Golden State warriors for three years in which time they won the NBA championship twice, she says being part of that moment was something she will never forget.

“To watch a group of people be that talented and to pull it together that consistently not not just once but twice I didn’t think I can ever explain how remarkable that feels, especially because it’s not my win, it belongs to the athletes, I got to be part of it because of them, it’s not mine. That I got to experience that and be there is such a gift.”

However despite the amazing high of an NBA championship win (and the shiny jewellery that goes with it) Chelsea says her biggest career high was actually something she experienced off the court.

“The highest moment for me was when I got to a place where culturally, I had learnt enough about my athletes to be able to serve them properly. It’s not just that we were different genders, they were also all different cultures and none of those cultures were mine. I honestly believe that to make a high performing person perform at their highest you really need to meet them as the person they are. Their motivations, their cultural needs, their family needs, their performance needs. After about the second year I finally felt like I was getting to that place, where I was reaching them at a level that was culturally appropriate. I wasn’t sure I would ever get there and if that was the case, then have I really served them? That’s not to say I know it all, I could spend another 20 years working there and not know everything, but to be able to understand where they are coming from enough to be able to give them what they need, that was my biggest high.”

After three years with the Golden State Warriors Chelsea was offered the role of executive director of athletic performance and sports medicine for the Atlanta Hawks. The Hawks had finished bottom of their conference and had the ambitious goal of turning their losing streak around with the aim of making it to the conference play-offs within three years. For Chelsea the opportunity embodied everything she loved about the NBA culture.

“They just kept raising the bar for you. Someone would say can you do this? How about this? Why don’t you have a go at that? Well if you did this then you must want to try that? The steepness of the learning curve is incredible but they support you and have so much trust in you. People expected things of me that I never even expected of myself that I had never imagined of myself, to this day it still feels a little bit make believe. But that was invaluable and it leaves you with this new look on life of why aren’t we having a go, why aren’t we pushing?”

“I went in as a high performance physio and came out six years later with a NBA vice presidency and I came out sitting in boardrooms learning the business of basketball because someone said well you have done that so why not give this a crack. They just keep pushing you and they place so much trust in you that you can do what they give you, further and doing more. when someone gives you that level of support it drives you.”

By the end of the three years the Hawks made it through several rounds of the playoffs to compete in the Eastern Conference finals, making them one of the top four teams in the NBA that season, a crowning achievement for the club. Chelsea meanwhile had been promoted to vice president of athletic performance and sports medicine. An executive position, and one of only two women at that level.

However the drive and opportunities came with sacrifices, the job was seven days and week up to 18 hours a day. And after three years in Atlanta, Chelsea and her husband were ready to come home. Right now she’s taking a break, allowing herself time to reflect on a whirlwind six years and the lessons she has learnt. Lessons she hopes to bring to her next role in New Zealand.

“I think for me the biggest learning was around the organisation of people and how you set the bar for them. You have meet firstly as humans, if you do that there isn’t anything blocking us from connecting. There’s absolutely no reason why a white woman, half aussie half kiwi who knows nothing about basketball can go into an established organisation with all its history, and within four and a bit years be sitting at the vice presidency table when she went in as the physio. That shouldn’t work, but it did and I have had to unpack that a number of times. I think it’s because once you break it down it’s about humanity. It takes some bravery to meet someone as human because it means accepting you are one too, but once you can find that common ground with people then you can build up from there, while that might be a real challenge it’s also where the real payoff comes from.”

“I think in Aotearoa we can sometimes pigeonhole people. We say you do this, and this is what you are capable of and please don’t step outside of that. What we need to start saying to people is well how far can you go? What tools and support can we give you? Can you do that? Why don’t you try this? If you do that in your organisation everybody wins. It takes bravery and belief and huge amounts of human investment, but the payoff is that people will achieve things they never thought they were capable of. As a country we can only benefit from that.”

MENU

MENU