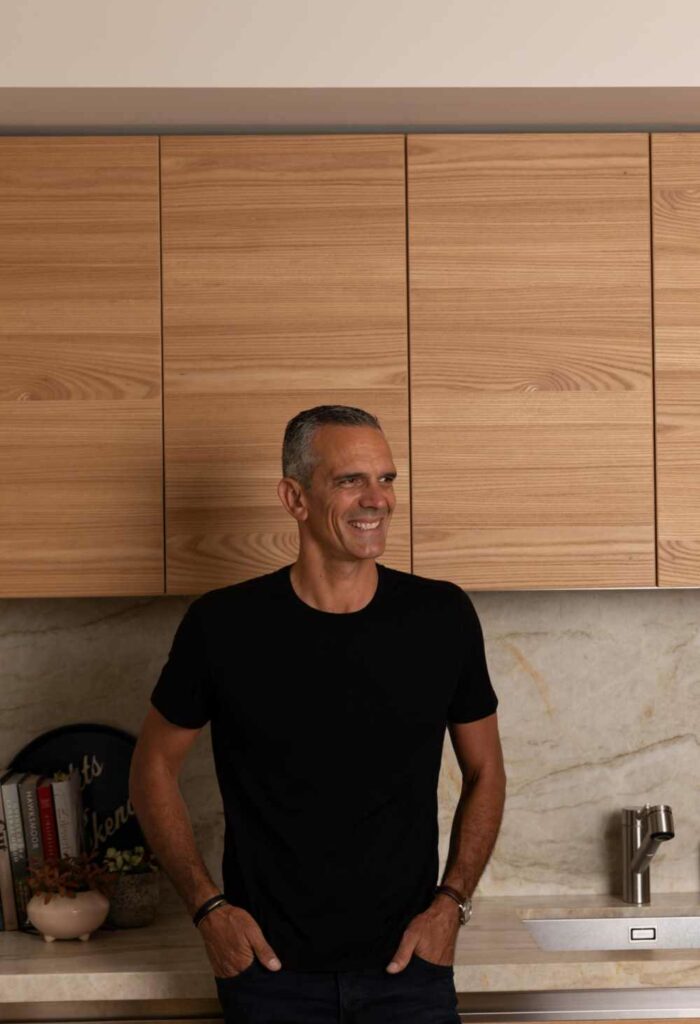

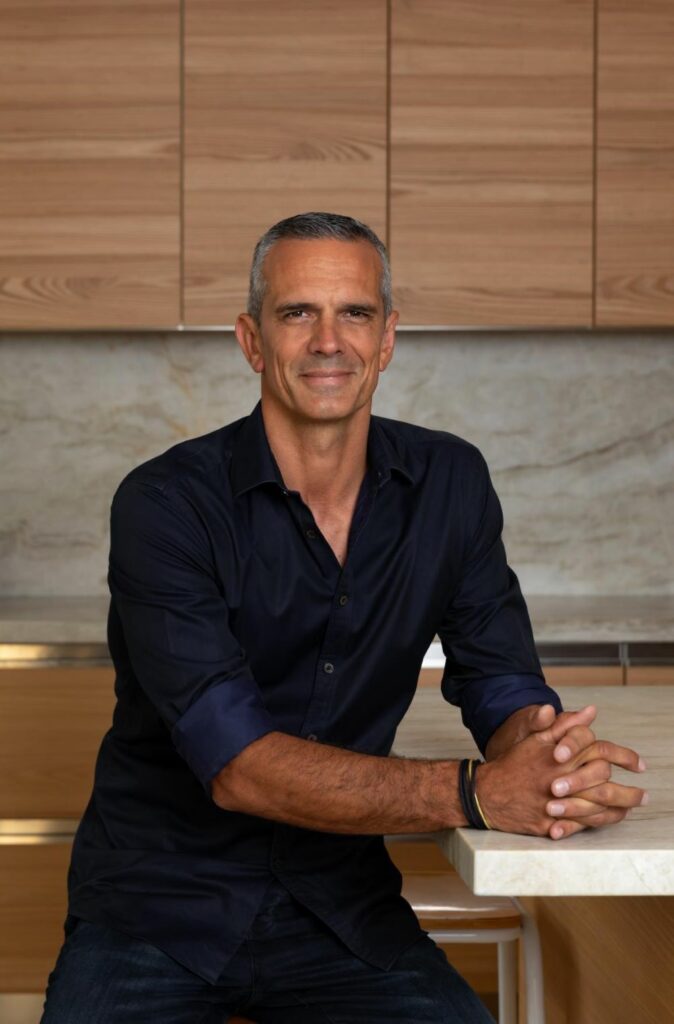

Josh Emett always wanted to be a chef. Brought up on a farm in rural Waikato, he was baking cakes at age six and loved fishing and hunting. He says his passion for cooking was fuelled by the wild produce around him and the desire to understand where it came from, how to use it and, most importantly, how to respect it.

“We had free reign in the pantry and the kitchen growing up, mum thought that would keep us out of trouble. We lived remotely on a farm and it was 20 minutes to the supermarket so we didn’t often buy all the food kids love like chips and biscuits. Instead, we learned to bake cakes, chocolate caramel slices, pavlova – you name it.”

His first job in a professional kitchen was at age 14 when he worked in a Hamilton retirement village washing dishes, setting up a food trolley and wheeling it down to a villa to serve 10 elderly women dinner.

From humble beginnings to Gordon Ramsay’s restaurants

Josh moved overseas in his early twenties, jumping between London and Melbourne where he worked in several restaurants under talented chefs. Eventually, he headed to the south of France to work as a chef on luxury yachts, saving enough money to move to London once again. Upon his return, Josh made the bold decision to ask British celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay for a job.

“I wanted to learn from and work under Gordon Ramsay so I rang the head chef at Restaurant Gordon Ramsay in Chelsea and he invited me to come in for a day. Gordon came and spoke to me and I told him what I wanted to do. The head chef asked me what position I wanted and I said ‘I’ll take what you’ve got’. At the time Gordon ran what was known as one of the most ferocious kitchens in the world but I knew I would gain so much from it.”

The humble Kiwi chef from rural Waikato joined Restaurant Gordon Ramsay in Chelsea as Senior Chef de Partie, working his way up the ranks in the kitchens of several of Ramsay’s restaurants before opening restaurants for Gordon Ramsay Holdings in New York, LA and Melbourne.

“I worked hideous hours for most of those years. It was full-noise and amazing. We were so focused on food and service. I spent a lot of my time in the dining room making sure the flow of food that comes from the kitchen and the style of service was aligned. I treated those businesses like my own, and Gordon encouraged me to do so.”

After 20 years of experimenting with European cooking styles Josh realised it was time to return home and explore New Zealand’s culinary scene. In 2012, Josh opened his first restaurant, Rātā, in Queenstown showcasing traditional New Zealand cultural traditions and local produce. His first Auckland restaurant, Onslow, allowed him to realise his dream of intertwining inspiration from Europe and Aotearoa.

“Coming back to New Zealand and opening restaurants here has been a real highlight of my career. Opening Onslow in 2020 during COVID and the opening of our most recent restaurant last year, Gilt Brasserie, are both really proud moments of doing something that has a really personal standpoint.”

Transitioning from chef to business owner

Josh says opening a restaurant is driven by more than just a love of cooking; it’s about a strong emotional connection to everything the business encompasses.

“A restaurant is not just a place to eat; it’s a performance, an experience, and a social hub that weaves people and communities together. But It’s also a terrifying ride, how will others perceive it? Will it survive? I love it when restaurants are humming – it’s high energy, bustling, and vibrant. In the industry, that’s what gives you a high. It’s a performance, there’s a lot of pressure. You are there to make people have a wonderful experience, but you can’t please everyone – which is often a good thing because you take feedback, do something with it and then improve.”

Pouring so much time, effort and love into something like opening a restaurant makes it difficult to relinquish control – especially as a business owner. Josh says transitioning from a chef to a business owner has its own unique challenges and that letting go is far from straightforward.

“You have to take a step back and allow your team to take over. Sometimes mistakes happen, but often people will excel when you give them the space to do that. Being open to change and upskilling yourself in managing people and how to be a great leader, how to manage a business, how to understand the finance… that’s the difficulty with restaurants, they are very complex businesses.”

Transforming Auckland’s neighbourhoods and communities

Josh’s goal with his restaurants is to grow New Zealand’s culinary scene to compete with great restaurants on an international scale and make it one Kiwi are proud of. But, even further, he wants to enhance Auckland’s vibrancy.

“Part of my responsibility is to build great restaurants in New Zealand, and Auckland specifically, because that is where we are focused. I want to continue to grow Auckland’s food scene and make the city a really vibrant place to live.

“When you live in a neighbourhood and someone opens a great local restaurant, everyone migrates to it. It starts to breathe life into areas and becomes a place that people go to socialise. They become those community hubs that when done well, people think ‘I live in the best area’. It completely changes the dynamic.”

And that’s exactly what Josh wants to achieve with his and Helen’s newest opening, Gilt Brasserie, a contemporary brasserie on Auckland’s Chancery Street. This area of Auckland bore the brunt of the pandemic, affecting several businesses and seeing the demise of a few restaurants because of it.

“Part of our work and our investment in that site is that we are going to reinvigorate that area of Auckland. There is already a great coffee shop on Chancery Street, a great bar, and we have just opened our restaurant. All of a sudden, it’s become a place to migrate towards.”

Josh highlights the impact of using the expertise and skills he acquired abroad in making his restaurants successful, and encourages aspiring individuals to extend their gaze beyond New Zealand.

“You have to be so deeply ingrained in the world of food – not just in New Zealand. You need to be in tune with what’s going on around the world, who’s doing what, who’s trying different techniques, how different businesses are being run and what equipment they are using. Food is constantly evolving.”

MENU

MENU